A British Broadcasting Corporation article, published on June 14, 2018, under the Science & Environment column reads: Einstein’s travel diaries reveal racist stereotypes. The article went on to reveal how the genius scientist’s private thoughts could easily have been read as racist –and indeed they were slurs! However, how many of us can boast of better private thoughts; genuine, noble, non-condescending private moments when we have not looked down on a fellow human being? Are we not all racists, as argued by Mona Chalabi? Going by this, it should then not be of any shock, if racism is reacted to with counter-racism.

In recent times, the talk of race discrimination has been more in the spotlight, not just in the United States, where it is being championed, but it is sweeping across many other climes. Racism has been with us since the very dawn of mankind, and it is somewhat expected, that people from different cultures act differently towards one another. Trust, personal and cultural differences are some of the factors that may bring about these actions; and for a long time, this was acceptable amongst many races, not just the so-called white supremacists. Indigenous Indians, according to American history, obviously thought, felt and acted differently to the strange bearded white skins that invaded and desecrated their lands. Even ethnic groups within the same geopolitical areas react differently to one another. It is human nature. Lower animals exhibit this behaviour as well. However, when such reactions degenerate to inhumane treatment to a fellow human or animal, or the one moves to dominate, control and debase the fundamental rights of the other; (as the case may be) -failing to see this counterpart as an equivalent, in essence, therein the problem lies.

There were, however, periods in the past, when racism was perfectly acceptable in society. It was arguably even fashionable to be racist once upon a time -it showed progressiveness, class, panache! It was easier to discountenance the other when “it” was considered property or chattel to be owned and used as seen pleased. While the views in this article do not in any way support racial discrimination, it will, however, be glib, to gloss over the controversial issue and consider it only from the present trend of discourse or trend set by modern society. And while racism and racial segregation were mostly seen as a one-sided street that only flowed from the top to the lower echelons, it most definitely was not. For if a person was mistreated by another, either in a position of power or authority, it only makes sense that due payback will be recompensed when or if the tables were ever changed. In short, discrimination and segregation are similar, though different, and it is a human attribute, not just a white thing. Even among folks of the same ethnicity, or people of colour, respect or otherwise is accorded as seen fit or dictated by society.

RACIAL STEREOTYPES IN MODERN NIGERIAN ART

Ben Enwonwu, an advocate of the Negritude movement, now known for his recent auction sale of £1,000, 000 (One Million Pounds) net hammer price, for the sale of a Tutu painting -a realistic painting of an Ile-Ife royal princess, and one of the three different versions of the icon Princess Tutu, painted in the early 1970s, is without any doubt, the most successful and revered modern Nigerian artist.

First Live Sketch of H.M. Queen Elizabeth II, 1958, (London), Graphite and Pastel on paper, 38x25cm & African Dancers, 1947, Gouache on paper, Private Collection, Lagos

Why then would I muddle up this beacon with a dark topic like racism, or ask if the most respected and most renowned Nigerian modernist had racial tendencies? Well, because he was human to start with, and it is human nature. More so, he was a victim of racial discrimination on many counts. Historians generally theorize that he pursued a degree in Anthropology because he wanted to better understand human beings, in an attempt to be objective at the unequal treatment meted to him, especially in the western world, and mayhap as well as at home. According to the leading Nigerian author on the artist; Sylvester Ogbechie, in his book Ben Enwonwu: The Making of an African Modernist, Kenneth Murray was displeased being treated equally with his mentee -the upcoming Ben, by being placed on the same salary as the other seasoned teachers; a significant issue which eventually resulted in a rift between the two subjects. So, if the greatest modern artist in postcolonial Nigeria was the subject of much discrimination, does it not stand to reason that he would have acted similarly in a position of power, or superiority?

According to Neil Coventry, Bonhams representative for West Africa and a leading private consultant on Ben Enwonwu, in a recent conversation on the artist, he believes Ben Enwonwu was in a class of his own and did not aspire to be treated equally with his western contemporaries. Coventry says he was better and I agree with him, the artist was sure of himself. Being treated as a colonial was not aspirational to him as he was in a class of his own, self-assured of his superiority amongst so-called contemporaries. His genius not just on the canvas could be ascribed to this. According to Neil, Enwonwu was so sure of his abilities that he was quoted to have said he could work in and with any medium. Indeed, he was a rare artist, as Nigeria had ever seen or had. His works across these media –wood, bronze, fibre, watercolour, oil, acrylics, pencil, etc. are testaments to his genius. He was so talented, protocols were broken for him, even as a man of colour.

According to Sylvester Ogbeche in an interview granted to mark the launch of his book, “Enwonwu is considered one of the greatest artists in African American culture”, he went further to call him “Africa’s greatest artist”. A reason for this according to the author can be ascribed to the fact that the Times Magazine was already featuring and doing reviews on Enwonwu’s works as far back as 1949 –a period in American history when African-Americans were striving for equal rights and representation. It stands to reason thus, if he saw himself as in a class of his own, above and beyond all others, not just his white contemporaries or even his fellow countrymen. Many first hand reports of interactions with the artist, including some of his surviving texts like: Into The Abstract Jungle: A Criticism of the New Trend in Nigerian Art, written by him and published in the June, 1963 issue of the Drum Magazine, where Enwonwu addressed other upcoming artists, portray the artist as very self-sure, perhaps even coming across as entitled.

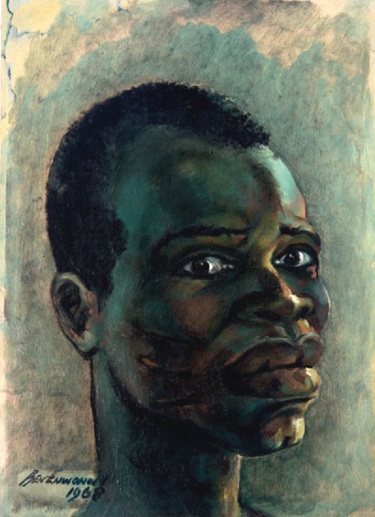

An analysis of his 1968 painting: Portrait of [the] Driver, from the Nigerian Art Digital Gallery, but now in an anonymous private collection would have been labelled as a racial depiction of a black person, if only it had been painted by another artist from a different race. According to Neil Coventry, recounting an earlier unconfirmed interview which the artist granted to Ogbechie, the painting depicts Isaiah a personal driver of the artist, depicted in exaggerated blackface stereotypes, coming off almost like a realistic caricature. The large over accentuated lips, as depicted by Richards and Pringle’s famous Minstrels depictions of black acts, the elongated forehead with receding hairline, the thick calloused tribal marks of the Yoruba region of Western Nigeria, heavy furrowed eyebrows and lower set ears, all driven home with a look of servitude and inferiority, set against a washed plain background helps to project the subject unflatteringly in the foreground. The unconfirmed story has it that the painting is a depiction of Enwonwu’s driver who was caught up in the Nigerian Civil War pogrom, which resulted in systematic ethnic cleansing by different ethnicities. Fortunately, the story ended well for the young driver, who managed to sneak away, in the chaos, perhaps thanks to his master, an Anambra native that may have been able to placate the situation with his fellow clan men.

An analysis of his 1968 painting: Portrait of [the] Driver, from the Nigerian Art Digital Gallery, but now in an anonymous private collection would have been labelled as a racial depiction of a black person, if only it had been painted by another artist from a different race. According to Neil Coventry, recounting an earlier unconfirmed interview which the artist granted to Ogbechie, the painting depicts Isaiah a personal driver of the artist, depicted in exaggerated blackface stereotypes, coming off almost like a realistic caricature. The large over accentuated lips, as depicted by Richards and Pringle’s famous Minstrels depictions of black acts, the elongated forehead with receding hairline, the thick calloused tribal marks of the Yoruba region of Western Nigeria, heavy furrowed eyebrows and lower set ears, all driven home with a look of servitude and inferiority, set against a washed plain background helps to project the subject unflatteringly in the foreground. The unconfirmed story has it that the painting is a depiction of Enwonwu’s driver who was caught up in the Nigerian Civil War pogrom, which resulted in systematic ethnic cleansing by different ethnicities. Fortunately, the story ended well for the young driver, who managed to sneak away, in the chaos, perhaps thanks to his master, an Anambra native that may have been able to placate the situation with his fellow clan men.

Notwithstanding, the rendition of the poor driver by his artist master did more than capture the situation. Had the painting been signed by a white artist, it may have been labelled racist, by today’s standards. This is not to say the artist was tribalistic, but perhaps depicts his level of understanding of the seriousness of the situation, and a perfect interpretation of his driver’s dread. A comparison of another portrait in the same private collection, executed barely half a decade before Isaiah’s portrait, portrays yet another of Enwonwu’s coloured subject in a better light. Claimed to be the portrait of a North-eastern African, with shoulders squared, chin high and painted at an elevated position, as opposed to Isaiah’s downward sweeping decline, this painting is also a realistic painting of a person of colour, but executed with dignity, even perhaps infatuation, as betrayed in the passionate sultry gaze of the subject at her artist.

Notwithstanding, the rendition of the poor driver by his artist master did more than capture the situation. Had the painting been signed by a white artist, it may have been labelled racist, by today’s standards. This is not to say the artist was tribalistic, but perhaps depicts his level of understanding of the seriousness of the situation, and a perfect interpretation of his driver’s dread. A comparison of another portrait in the same private collection, executed barely half a decade before Isaiah’s portrait, portrays yet another of Enwonwu’s coloured subject in a better light. Claimed to be the portrait of a North-eastern African, with shoulders squared, chin high and painted at an elevated position, as opposed to Isaiah’s downward sweeping decline, this painting is also a realistic painting of a person of colour, but executed with dignity, even perhaps infatuation, as betrayed in the passionate sultry gaze of the subject at her artist.

One thing seems to be sure though, whether carving wood, sculpting what many see as an Africanized queen, or painting a portrait, (of terrified Isaiah or an alluring love interest), Ben Enwonwu will remain one of the greatest artists of all time – one that cannot be contained or summed up by a single attribute as preoccupation with race.